The Indian polity, a democratic diagnosis

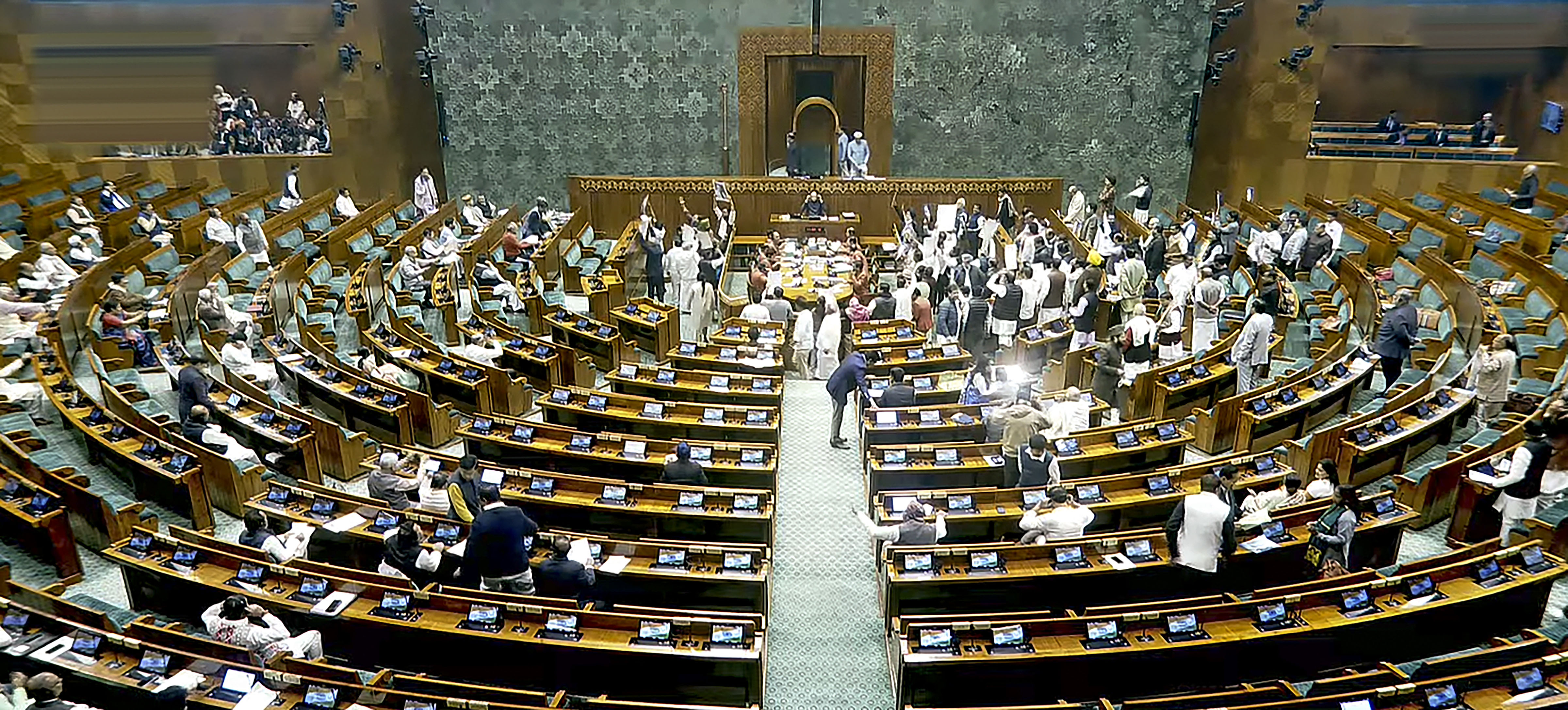

The HinduAn opinion article, last month, in one of India’s main English dailies, summed up the emerging prospects succinctly: ‘A parliamentary majority is being used as a bulldozer to fashion an autocracy, the new India version of a presidential form of governance…The replacement, at the forthcoming inaugural, of the real president of the Indian republic by the prime minister may symbolise more than the ego of an individual’. One consequence of this trend, reflective of the unease generated by it, is a statement in the shape of a letter written to the President of India recently by a group of former civil servants expressing concern over attempts by the government to change the character of the civil service and its functioning, leading to the civil servants being ‘torn between conflicting loyalties’, thereby weakening their ability to be impartial. In his tome published last year, Christophe Jaffrelot analysed the Hindutva ideology based on Israeli scholar Sammy Smooha’s theory of ethnic democracy — defined as the ideology of a group that considers itself bound by racial, linguistic, religious or other cultural characteristics with a sense of superiority and rejection of the ‘Other’ generally perceived as a real or perceived threat to the survival and integrity of the ethnic nation.’ The conflation between nationalism and Hindutva has been the backbone of the new hegemony that has been of immense help to the Bharatiya Janata Party in projecting a potent conjoint image of Hindutva and development. The formal equality of the two Houses seems to have been done away with and the Leader of the Lok Sabha in his oration could have suggested, measures to increase the working days to 90-100 days as in the past, initiate the practice of having a Prime Minister’s Question Hour each week in both Houses, and proposed more effective measuring for the functioning of the Committee system to enhance its effectiveness and public confidence.

History of this topic

'India’s Independence will be in jeopardy if parties place creed above country', says V P Jagdeep Dhankhar

New Indian Express

Democratic polity witnessing a new low: Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar

Hindustan Times

The tactically silent Indian Muslim voter

Hindustan Times

Symbols and substance: on the inauguration of the new Parliament building and beyond

The Hindu

Will new Parliament building stand the ‘test of democracy’?

Hindustan Times

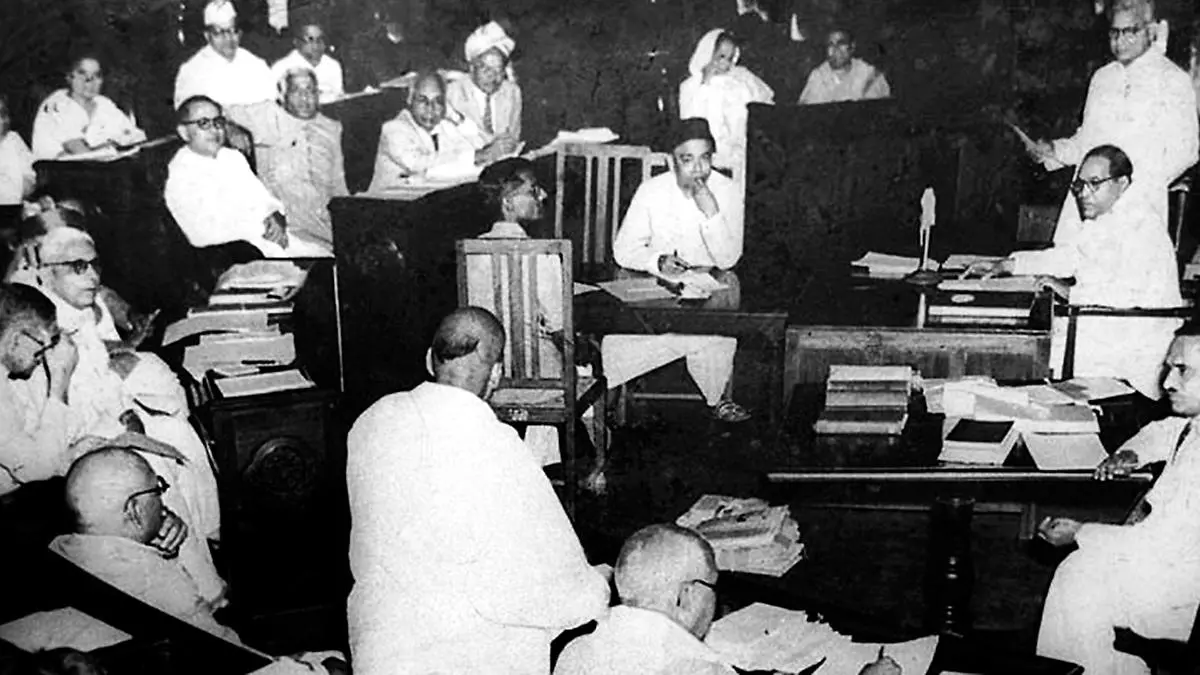

Book Review: ‘House of the People: Parliament and the Making of Democracy’ by Ronojoy Sen provides a ringside view of democracy

The Hindu

There’s genuine social mixing only at the polling booth: Mukulika Banerjee

The Hindu

India’s democracy, diminished and declining

The Hindu

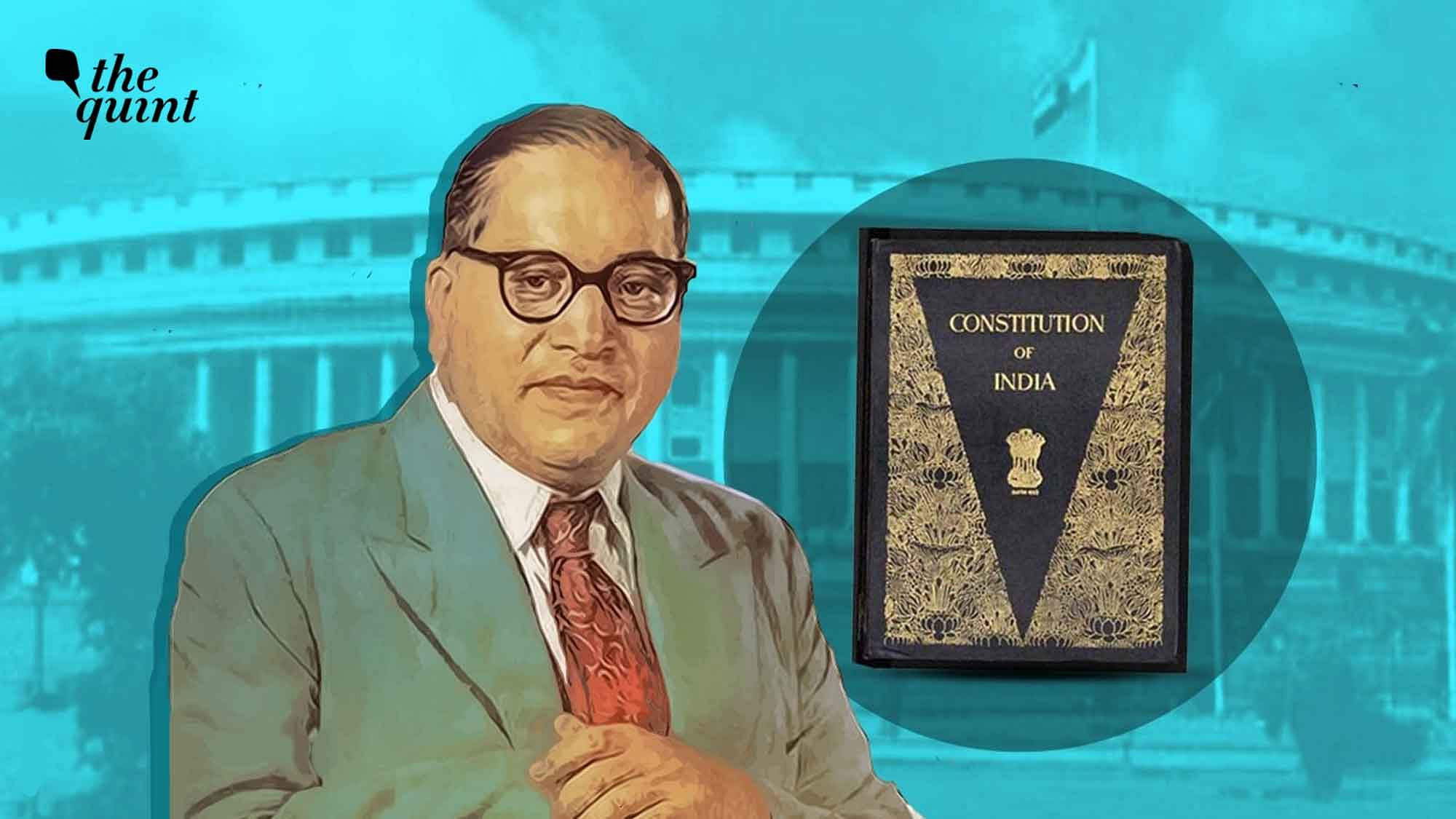

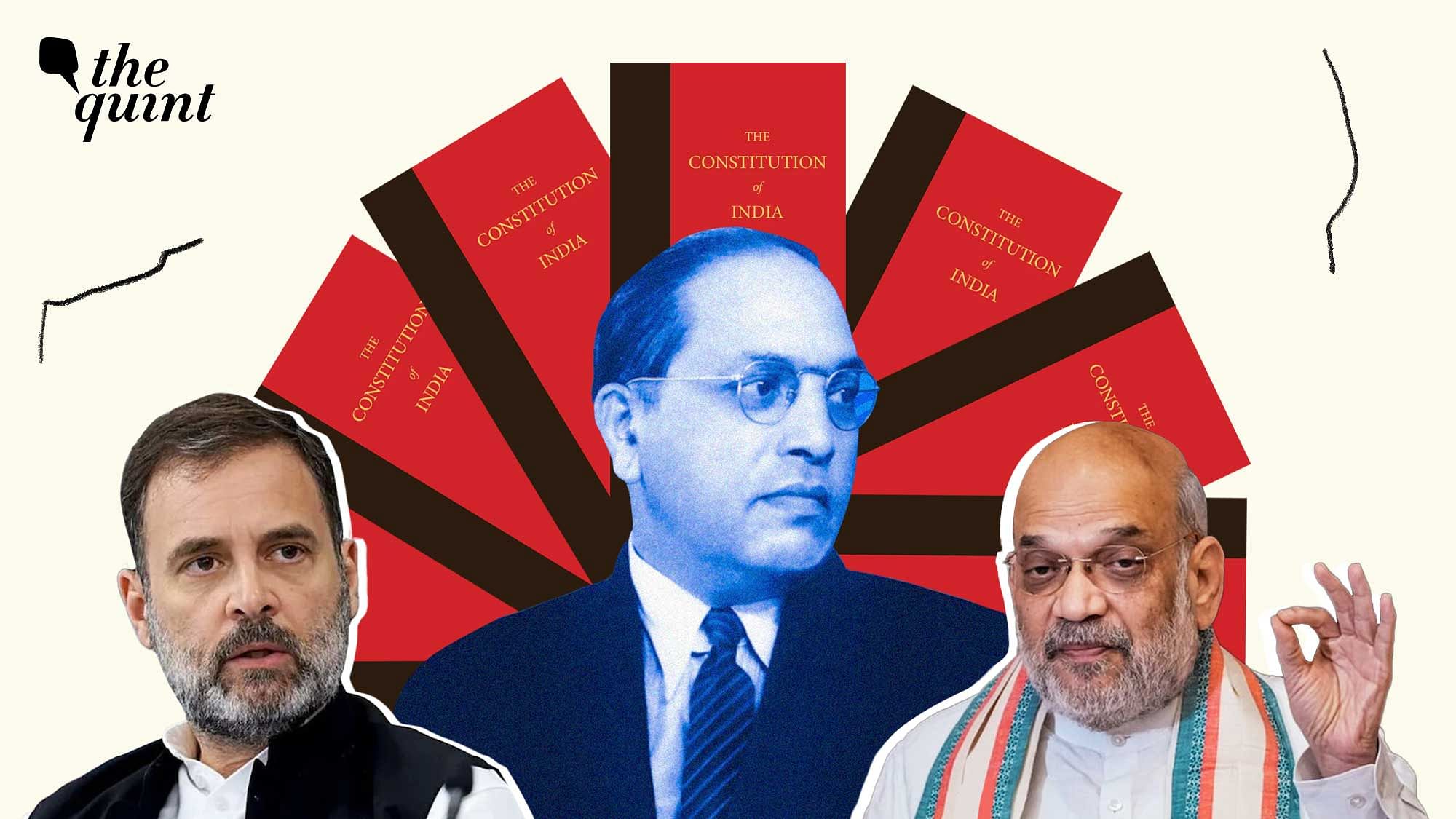

India’s ‘Controlled Democracy’: Has Our Legislature Been Rendered Irrelevant?

The Quint)

Yogendra Yadav's Book Explains Why Social Inequality is the Biggest Pitfall of Indian Democracy

News 18Discover Related