Most of Russia’s opposition leaders are dead, in exile or in prison. What happens now?

LA TimesA tribute to the late Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny, who died in an Arctic prison colony, is left near the Russian Embassy in London. “This is a very difficult loss for the Russian opposition.” The biggest problem that has plagued the opposition, said University of North Carolina political science professor Graeme Robertson, author of a book about Putin and Russian politics, “is that it has been unable to break out from small liberal circles to attract support from the broader population.” Khodorkovsky, who lives in London, is one of several Russian opposition politicians trying to build a coalition with grassroots antiwar groups across the world and exiled Russian opposition figures. Squabbling among the opposition, “doesn’t help,” said Nigel Gould-Davies, a former British ambassador to Belarus and senior fellow for Russia and Eurasia at the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London. But, even if the opposition were united, he questioned whether “given the instruments of coercion, repression and intimidation available to the Russian state, what difference, at least in the short term, would that make?” Three decades of Putin Putin is eyeing at least another six years in the Kremlin, which means he could effectively rule Russia for almost three decades. Although Navalny had his finger on the pulse, and his team succeeded in widely publicizing the investigation, the anticorruption message ultimately failed to produce political change inside Russia, Robertson said, because most Russians “know their country is badly governed and that their elite is corrupt, but they don’t see it being any other way.” In the three years since Navalny was jailed, Russian authorities have introduced more laws tightening freedom of speech and jailing critics, often ordinary people, sometimes for decades.

History of this topic

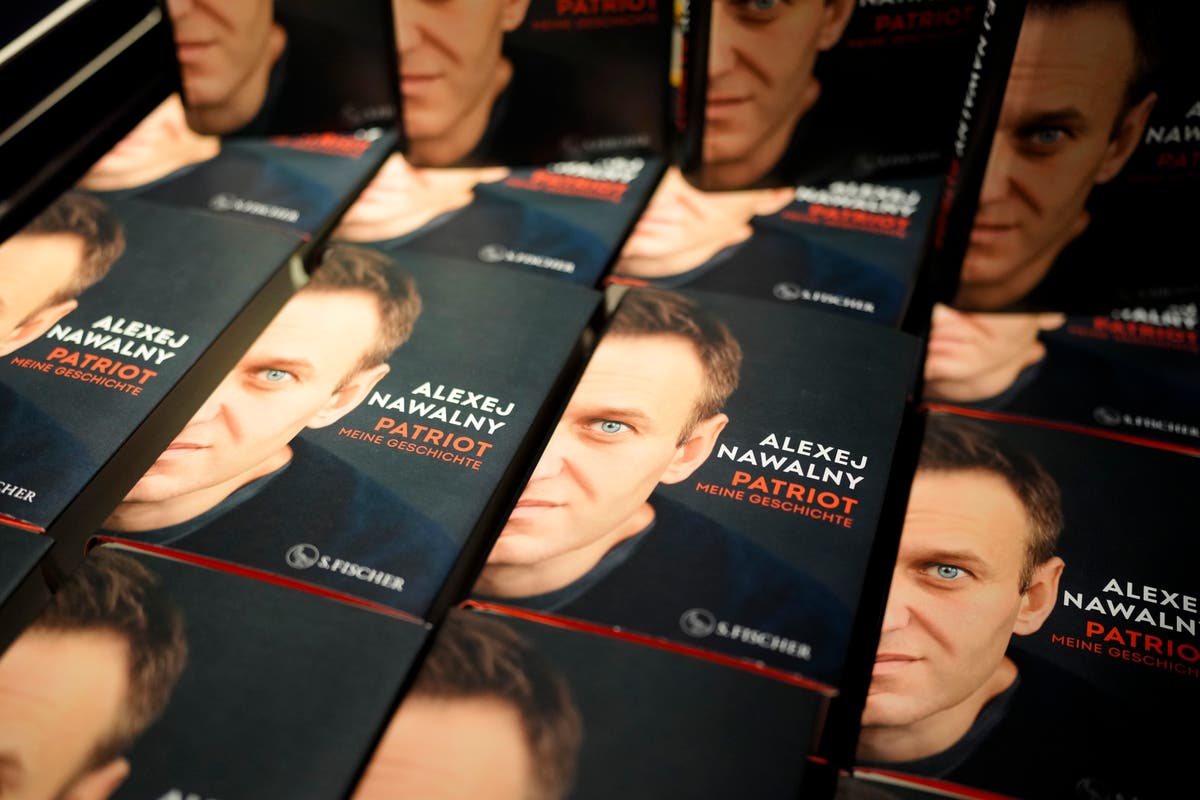

A Testament to Resilience: Alexei Navalny's Memoir Offers Inspiring Insights into the Struggle for Freedom and Democracy

The Hindu

A Testament to Resilience: Alexei Navalny's Postponed Memoir Offers Insight into a Life Lived in Perilous Times

Hindustan Times

Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny's posthumous memoir is a testament to resilience

The IndependentA Testament to Resilience: Alexei Navalny's Memoir Offers Inspiring Insights into the Struggle for Freedom

Associated Press

Russian opposition leader Navalny believed he would die in prison, excerpts from his memoir show

LA Times

Russia adds Navalny's widow Yulia Navalnaya to 'terrorists and extremists' blacklist

New Indian Express

Putin likely didn’t order death of Russian opposition leader Navalny, U.S. official says

LA Times

Vladimir Putin has been fighting not just Ukraine, but his own people

Live Mint

Russia extends deadline for preliminary probe into Kremlin foe Navalny’s death in prison, ally says

Associated Press

Russian President Vladimir Putin breaks silence on rival Navalny's death in prison: ‘It happens…’

Hindustan Times

Putin Says He Agreed to Navalny Prisoner Swap

Live Mint

Commenting on Navalny's death for first time, Putin says he supported prisoner swap for his foe

New Indian Express

Vladimir Putin: The autocrat eyeing a new world order

New Indian Express

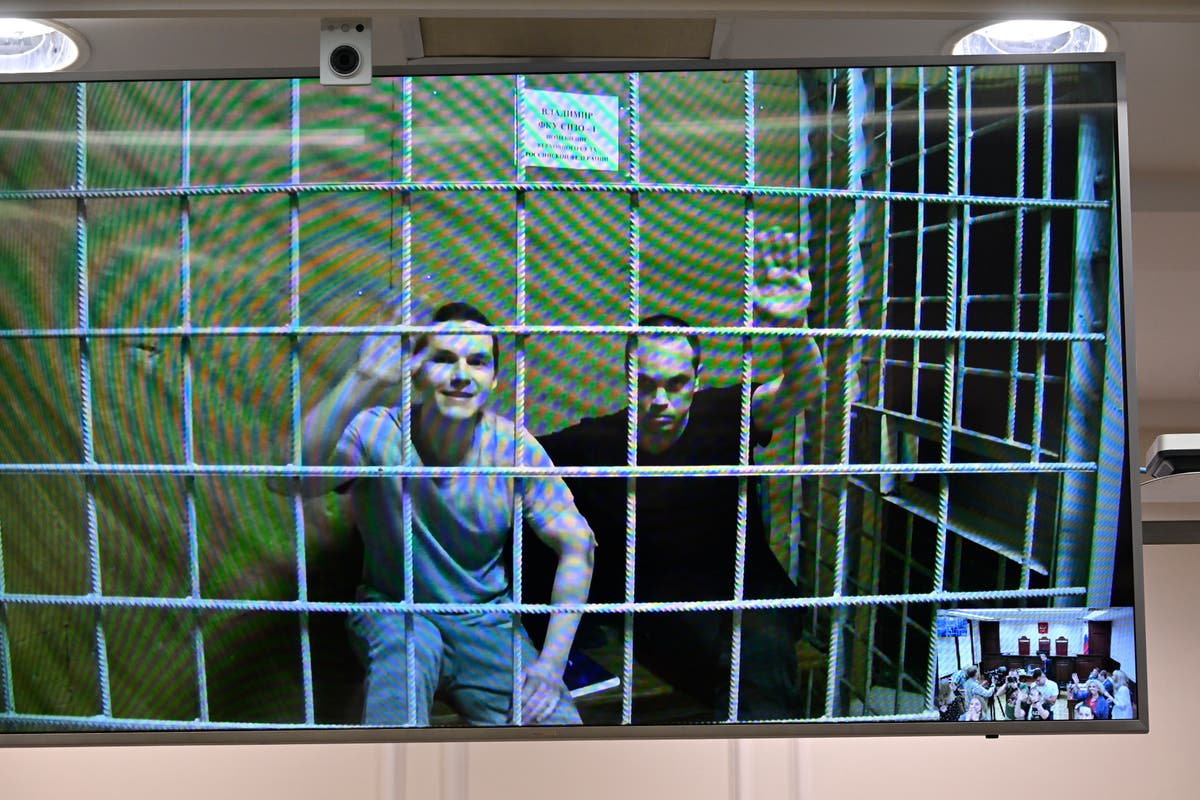

Who are the Russian dissidents still serving time after Alexei Navalny died behind bars?

LA Times

Putin critic Alexei Navalny 'died his own death', says Russian spymaster

India TV NewsRussian spymaster said opposition leader Alexei Navalny died of natural causes

Associated PressAP PHOTOS: Russians say final farewell at funeral of opposition leader Alexei Navalny

Associated PressAlexei Navalny laid to rest in funeral attended by thousands

Associated Press

Putin foe Alexei Navalny is buried in Moscow as thousands attend under heavy police presence

LA Times

Russian opposition leader and Putin critic Alexei Navalny laid to rest in Moscow | WATCH

India TV News

Alexei Navalny’s funeral to be held on March 1, says spokesperson

The Hindu

Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny's funeral to be held in Moscow on Friday

India TV News

Navalny aide says the Russian opposition leader was close to being freed before his death

Hindustan TimesNavalny aides say the Russian opposition leader was close to being freed before his death

Associated PressNavalny was close to being freed in a prisoner swap, claims ally

The Hindu

Navalny was close to being freed from prison before his death, says ally

Al Jazeera

A swap for Navalny was in the final stages before the opposition leader's death, an associate says

New Indian Express

Alexei Navalny's body handed over to his mother weeks after death inside prison

India Today

Russia threatening to bury Alexei Navalny on prison grounds, says his team

Hindustan Times

Russian cultural figures seek release of Navalny's body

The Hindu

Vladimir Putin has been fighting not just Ukraine, but his own people

Hindustan Times

The lonesome death of Alexei Navalny: Russia is back to its old ways

Live Mint

Alexei Navalny death latest: UK first country to issue sanctions over killing of Putin critic in prison

The Independent

Alexei Navalny – the man who knew too much

The IndependentWho are other Russian dissidents besides the late Alexei Navalny?

Associated PressMost of Russia’s opposition is either dead, in exile abroad or in prison at home. What happens now?

Associated Press

Alexei Navalny's widow claims he was poisoned, seeks 'punishment' for Putin

India Today

Alexei Navalny’s widow vows to keep fighting Kremlin, punish Putin for his death

LA TimesOver 300 detained in Russia as country mourns the death of Alexei Navalny, Putin’s fiercest foe

Associated PressAlexei Navalny mocked Vladimir Putin regularly — in Russia, dissent can come with lethal consequences

ABC

Alexei Navalny's team confirms his death, whereabouts of body remain unclear

India Today

In Russia’s Arctic area, Alexei Navalny’s mother searches for her son’s body

LA Times

Western officials and Kremlin critics blame Putin and his government for Navalny's death in prison

New Indian ExpressAlexei Navalny was 'the president Russia never got'. His death means a void in the fight against Putin

ABCAlexei Navalny's team confirms his death, demands body be returned to his family

ABC

Will the death of Alexey Navalny change Russian politics?

Al Jazeera

AP PHOTOS: With candles and flowers, thousands pay respects to Russia's Navalny

The Independent

With Alexei Navalny’s death, Russia has taken another step into Stalinist barbarity

The Independent

Putin critic Alexei Navalny dies. Who are other jailed Oppn activists in Russia?

Hindustan TimesDiscover Related

)

)

)