Is There Room for the US in Central Asia?

The DiplomatOn September 14, 2022, the House Foriegn Affairs subcommittee on Asia, the Pacific, Central Asia, and Nonproliferation met in a room in the Rayburn House Office Building across the street from the U.S. Capitol to hear testimony from key U.S. officials who deal with Central Asia. Bera then said that recent developments – the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, unrest in Kazakhstan in January, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine – “have foisted Central Asian countries into the global spotlight.” “But,” he continued, “it behooves us to have a sustained comprehensive approach toward this dynamic region based on its own merits.” And just as Bera had prefaced the notion of paying attention to Central Asia “based on its own merits” with a discussion of its geopolitical position, the subcommittee’s ranking member, Rep. Steve Chabot of Ohio, followed by focusing on the region’s geopolitical position, and, of course, China. As the United States engages in great power competition with the People's Republic of China and its partners in despotism – Iran and Russia – Central Asia is poised to be of critical importance in the years ahead.” In noting that Iran was, at that very moment, in the process of joining the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, Chabot made a callback to the days of the George W. Bush administration: “Iran is set to become a member of the, bringing together the world's new axis of, if not evil, true malevolence.” Chabot, a Republican, pivoted into a counterterrorism discussion and fired a few broadsides at the Biden administration for the withdrawal from Afghanistan. He then tipped his cards and noted that he co-chairs the Kazakhstan Caucus and stated, without apparent irony, “I hope that the reforms that that country is undertaking now will bring it closer to the West.” Chabot had nice things to say about Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, too, the latter being “the most welcoming partner when it comes to counterterrorism in the region.” Chabot’s remarks, more so than Bera’s, highlight a core tension in U.S. engagement with Central Asia: In order to engage with the states of Central Asia the United States has to effectively turn a blind eye to the very reasons the region is so closely aligned with “malevolent” actors – even more than simple geopolitics, it’s autocratic synergy at work. Four of the five Central Asian countries have seen violent unrest in the past two years and repression of individuals for their religion, gender, political activities, or sexual orientation is widespread.” He did not dwell on it long, however, returning within a few sentences to what remain the United States’ core concerns when it comes to Central Asia: “We are increasing our engagement in the region to demonstrate that we are a reliable partner and an alternative to Russia and to.” The price of being an alternative to Russia and China as a partner for Central Asia is ignoring the elephant of dwindling democracy in the room and hoping no one gets crushed.

History of this topic

The US Risks Irrelevance in Asia

The DiplomatFaced with threats from Russia and its Asian supporters, NATO and Indo-Pacific partners get closer

Associated Press

Could Iran Be a Gateway for Central Asia?

The Diplomat

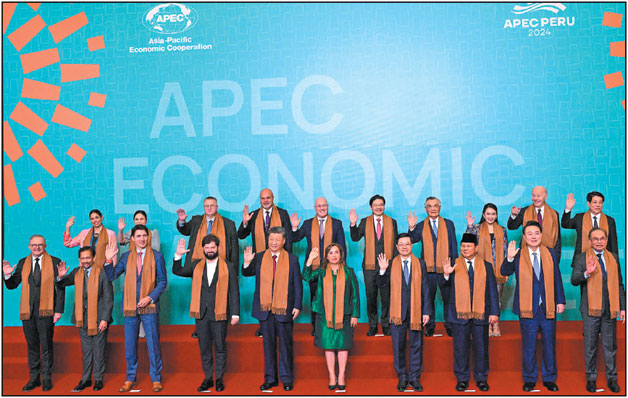

Regional countries must guard against US ploy to destabilize Asia-Pacific

China Daily

The West Is Eying Closer Relations With Central Asia

The Diplomat

Where Will the US Rank Asian Interests in the Midst of a Multi-theater Conflict?

The DiplomatThe US is welcomed in the Indo-Pacific region and should do more, ambassador to Japan says

Associated Press

Decoding America’s Central Asia policy

Hindustan Times

China-Europe Competition in Central Asia

The Diplomat

How Does China Approach Central Asia?

The Diplomat

Washington can't rupture peace in Asia-Pacific

China Daily

Washington can't rupture peace in Asia-Pacific

China Daily)

Is Central Asia still 'central' in Eurasian geopolitics?

Firstpost

Implications of China’s increasing security footprint in Central Asia

Hindustan Times

US Influence in Southeast Asia Waning

The Diplomat)

West Asia is looking for new friends and China is making the most of it

Firstpost

Asia Strains to Adapt to US Pushback Against China

The Diplomat)

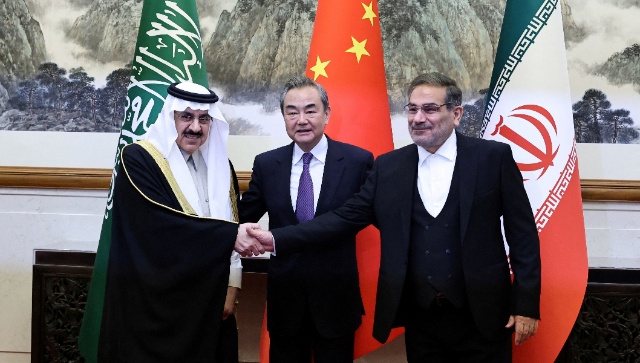

China-brokered Saudi-Iran détente is much more than a diplomatic breakthrough; it challenges US-led international order

Firstpost

New reality: The Hindu Editorial on Saudi Arabia-Iran reconciliation and China’s role

The Hindu

What Does Xi Jinping’s Visit Tell Us About China’s Relationship with Central Asia?

The Diplomat

China’s Wang Yi slams U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy ahead of Quad meet

The Hindu

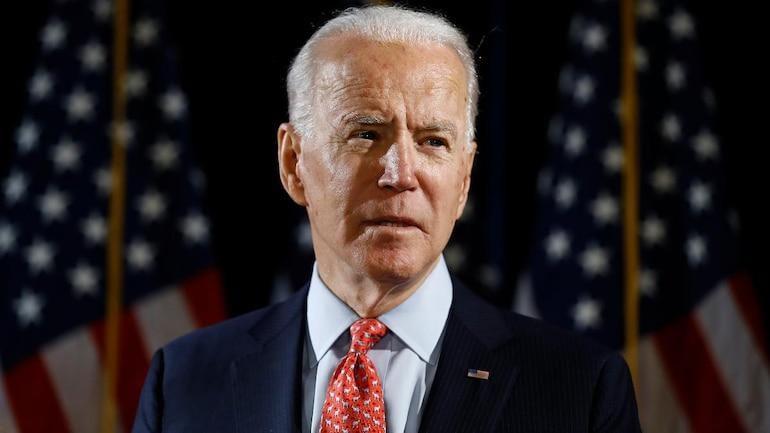

How different is Joe Biden’s ‘pivot to Asia’ from predecessors?

Al Jazeera

US to remind China of Pacific interests amid Ukraine tension

Associated Press

A new overarching Asian order

Hindustan Times

Deeply concerned by China's coercive actions, says Joe Biden at East Asia Summit

India Today

Afghanistan's neighbours wary as US seeks nearby staging area

India Today

As US pulls back in MENA, China, Russia may step in: General

Al Jazeera

Beijing warns US, Japan against collusion vs China

Associated PressNew phase of U.S.-China ties comes with tests for India

The Hindu)

China Expanding Role in South Asia, Region to Be More Contested in Coming Decades: US Think Tank

News 18Discover Related

)

)

)

)

)

)

)