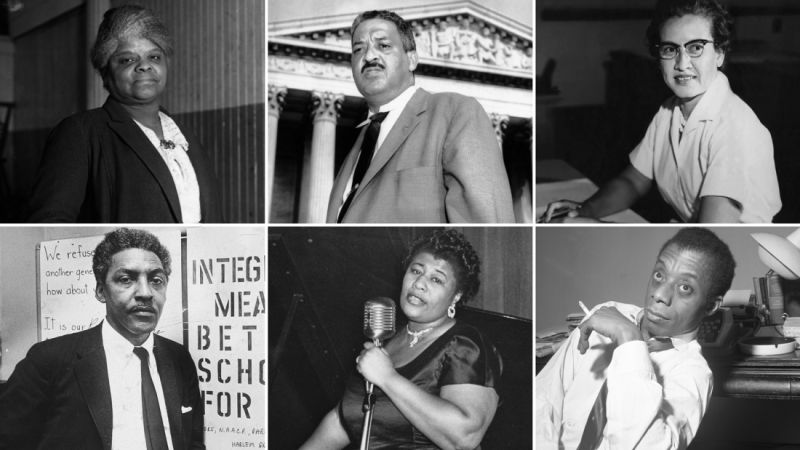

Op-Ed: As Confederate statues fall, build monuments to Black heroes at risk of being forgotten

LA TimesA few sites, like the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala., highlight some history of enslaved Africans and their descendants in the U.S. On the night of Jan. 8, 1811, a mixed-race man named Charles Deslondes led a group of people in an attack on a plantation owner in lower Louisiana that became the largest uprising of enslaved people in American history, and the first that required the intervention of the U.S. Army. There, on a modest plaza, 19 carefully sculpted Black busts perch atop metal spindles, with Deslondes front and center with a plaque bearing his name above the word “Leader.” The scarce public commemoration of Deslondes and his freedom fighters is emblematic of a much larger crisis of memory. African Americans carried this call forward in the next century, as when James Forten, Richard Allen and other Philadelphians wrote that “our ancestors were the first successful cultivators of the wilds of America” and their descendants were therefore entitled “to participate in the blessings of her luxuriant soil.” Roughly a century later, in 1924, the Black scholar W.E.B. Du Bois called for recognition that “it was black labor that established the modern world commerce which began first as a commerce in the bodies of the slaves themselves.” In the 1960s, the Black historian Benjamin Quarles wrote that “if in the eyes of the world today the United States stands for man’s right to be free, certainly no group in this country has sounded this viewpoint more consistently than the Negro.” Restorative messages like these are winning grudging acceptance in our history books.

History of this topic

Discover Related

)

)

)