The inside story of how Sandra Day O’Connor rebuffed pressure from Scalia and others to overturn Roe v. Wade

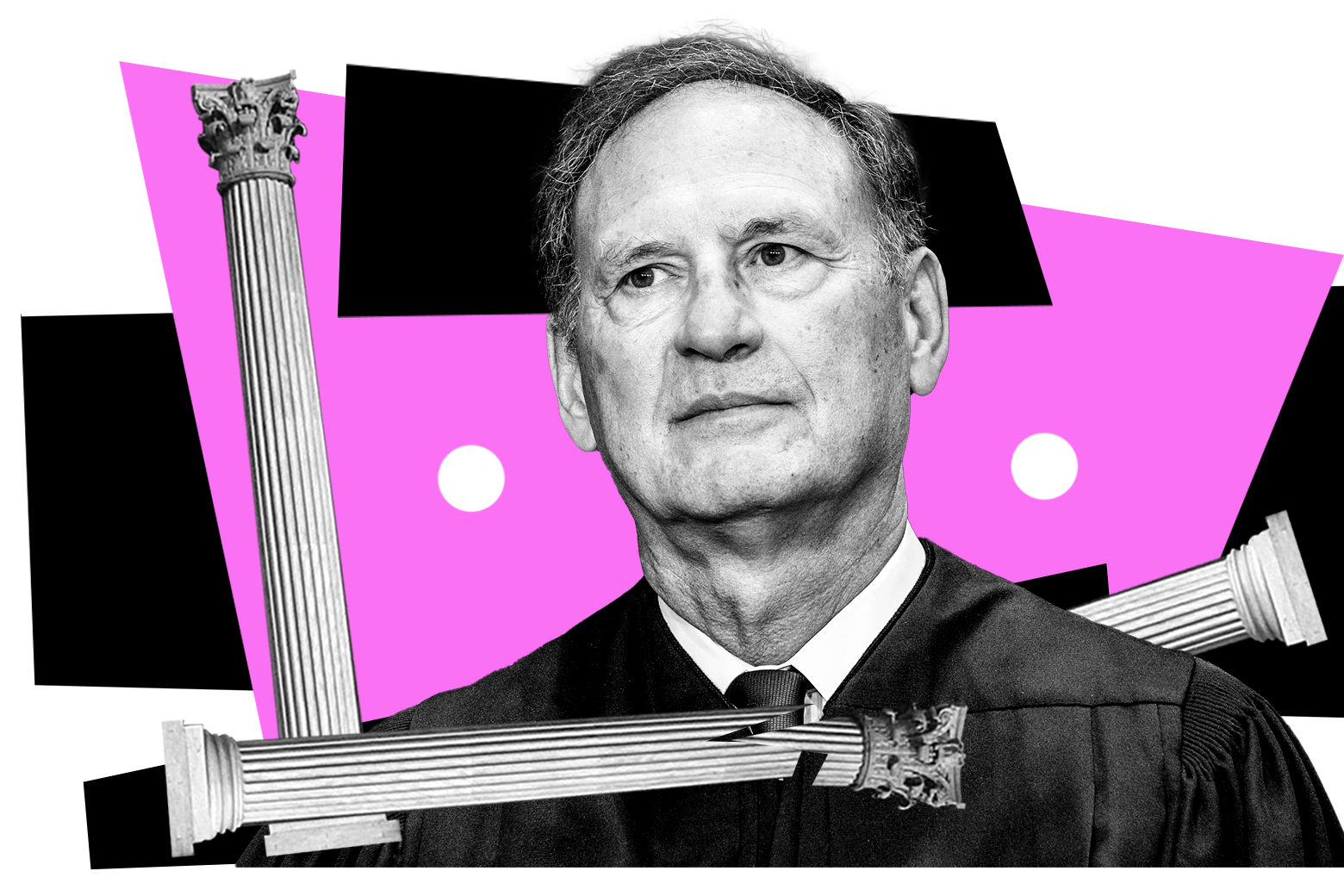

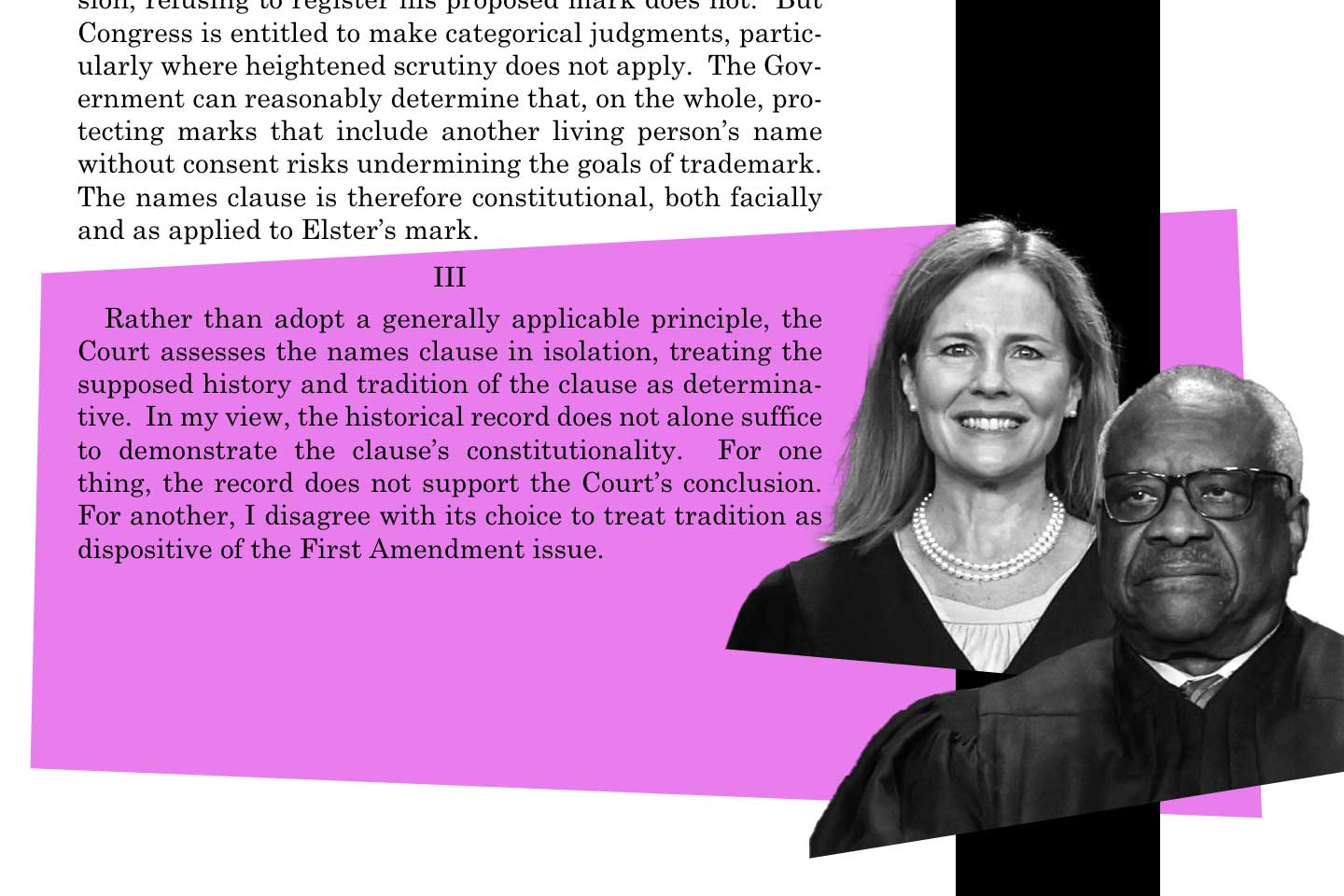

CNNCNN — During much of the 1980s, Justice Sandra O’Connor, the first woman on the Supreme Court, cast a consistent vote against abortion rights. O’Connor wrote in a 1983 case from Ohio that, as medical advances moved the point of viability up earlier in a pregnancy, the trimester approach was “clearly on a collision course with itself.” She reiterated her criticism of Roe in 1986 when she dissented in a Pennsylvania dispute, writing, “The State has compelling interests in ensuring maternal health and in protecting potential human life, and these interests exist throughout pregnancy.” By the time of the 1989 Webster v. Reproductive Health Services case, however, two additional Reagan appointees had joined the bench, and they appeared poised to help create a new majority to overturn Roe. Roe I has the great advantage, as far as I’m concerned, of being more obviously made-up.” Within a few weeks, as he drafted his own opinion, Scalia would deem O’Connor’s approach “irrational” and say it “cannot be taken seriously.” But in this first private exchange with his colleagues in May, he explained that his objection was that Roe lacked constitutional legitimacy “since it is based neither upon constitutional text, nor upon plausible constitutional theory, nor upon societal tradition.” “Until that error is corrected – until we make clear that it is not our job generally to decree what is ‘sensible’ – the public perception of this Court as an institution will continue to be grotesquely distorted as we have seen in the past year,” Scalia wrote in his May 23 note, bemoaning that his colleagues might be unable to “muster sufficient resolve to overrule, rather than heap error upon error with Roe II.” Two days later, on May 25, when Rehnquist sent his draft to the full court, his tactics provoked a sharp response from the liberal dissenters. “As you know, I am not in favor of overruling Roe v. Wade,” Stevens wrote, “but if the deed is to be done I would rather see the Court give the case a decent burial instead of tossing it out the window of a fast-moving caboose.” Likely sharing some of that latter sentiment, O’Connor in the end stripped Rehnquist of a court majority for the “deed.” Rehnquist was left with a plurality for his full opinion. When all the opinions were released on July 3, 1989, O’Connor had joined Rehnquist in upholding the Missouri law, writing in a concurring statement, “It is clear to me that requiring the performance of examinations and tests useful to determining whether a fetus is viable, when viability is possible, and when it would not be medically imprudent to do so, does not impose an undue burden on a woman’s abortion decision.” But she separated herself from the chief justice and the others on the right wing by leaving Roe v. Wade intact.

History of this topic

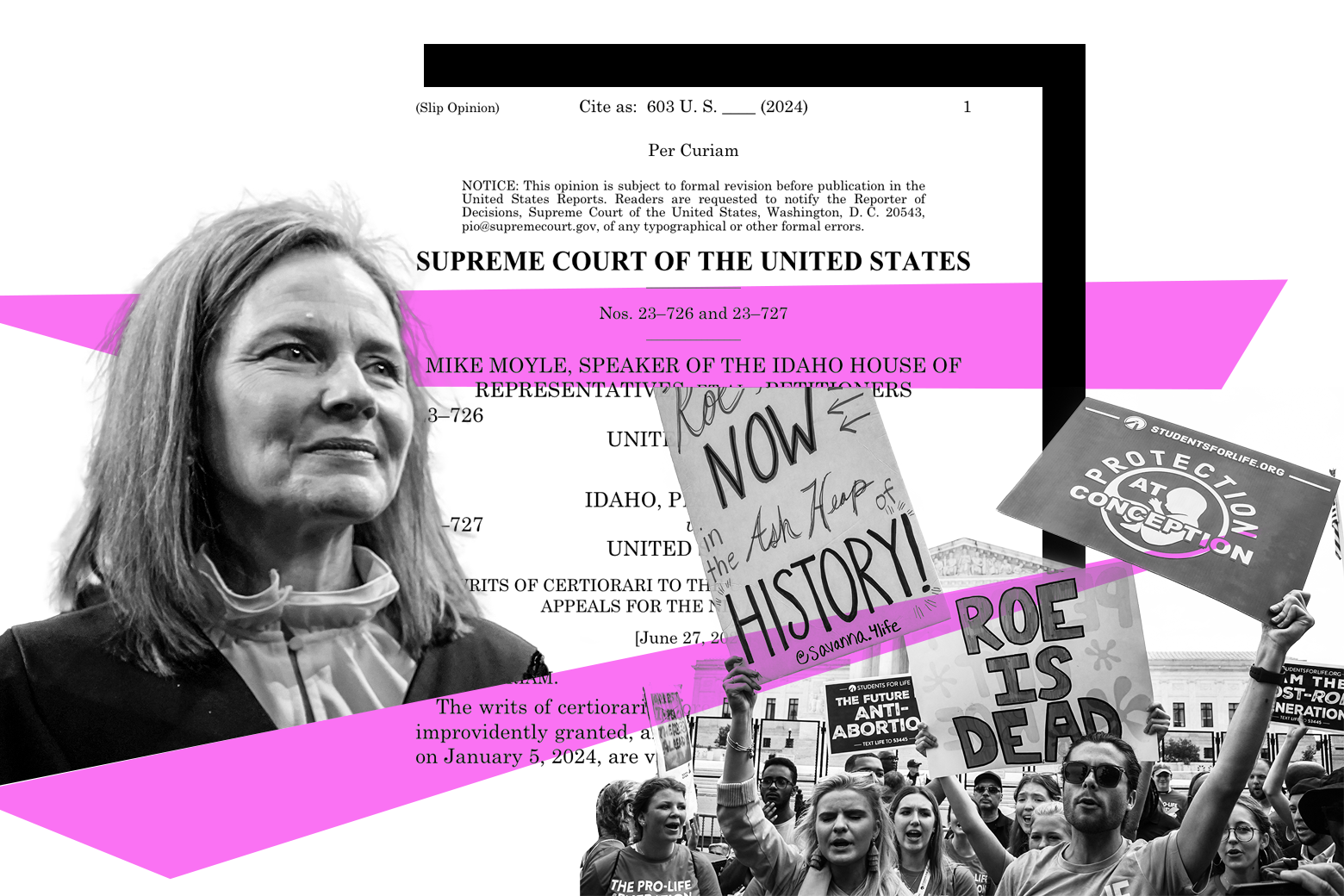

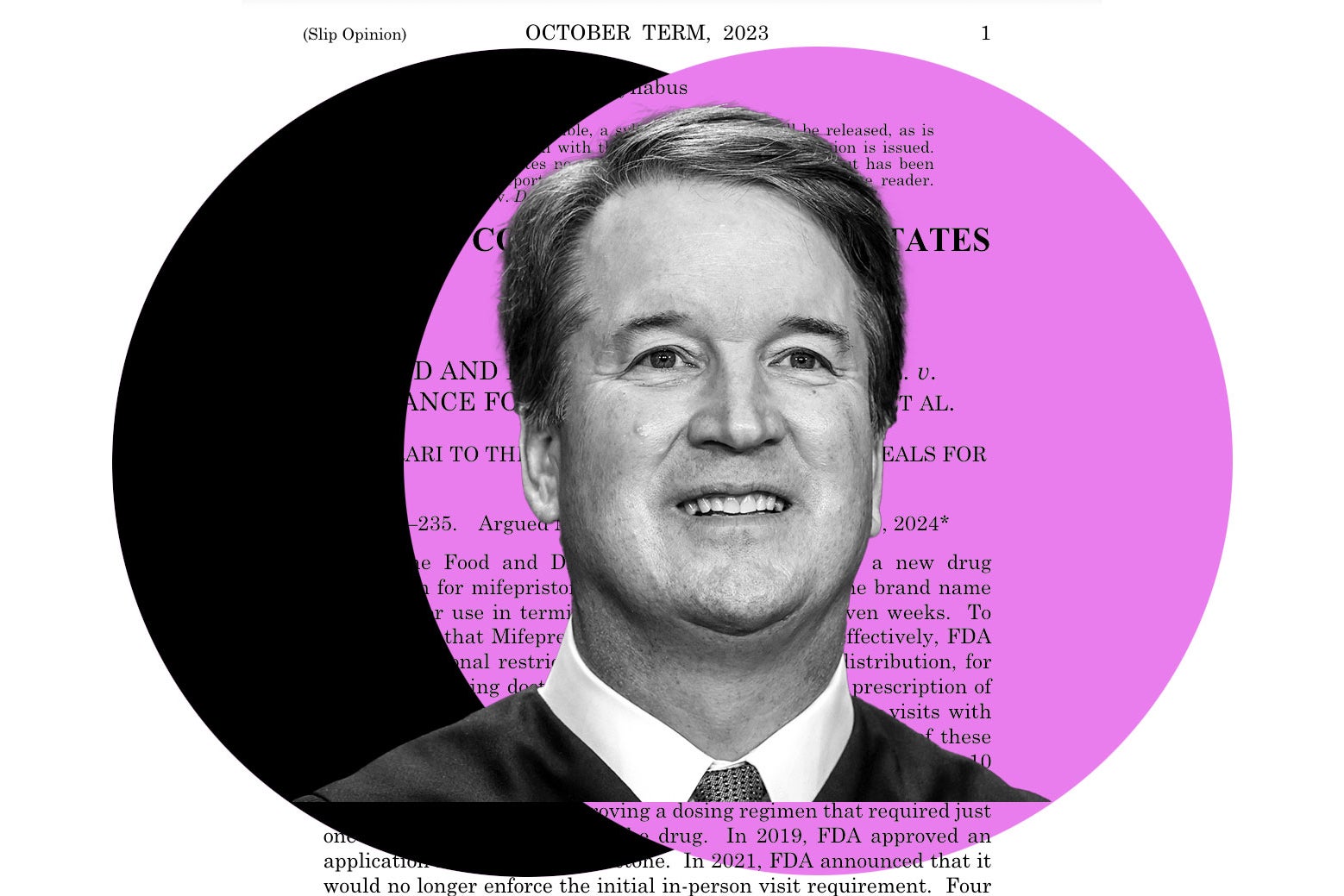

Roe v Wade overturned: Read the Supreme Court’s ruling in full

The Independent

Excerpts from the Supreme Court’s landmark abortion decision

Associated Press

U.S. Supreme Court overturns landmark Roe v. Wade ruling on abortion rights

The Hindu

Photos: ‘Overruled’ – Top US court banishes abortion law

Al Jazeera

Decoding the abortion tussle as Roe v Wade likely to be overturned

Hindustan Times

Leaked initial draft says Supreme Court will vote to overturn Roe v Wade, report claims

The Independent

Opinion: The memo that saved abortion rights in America

CNNDiscover Related

.jpg?w=1200&ar=40%3A21&auto=format%2Ccompress&ogImage=true&mode=crop&enlarge=true&overlay=false&overlay_position=bottom&overlay_width=100)