Salman Rushdie’s Victory City is ‘a restoration of the powers of fiction in these censorious times’

The HinduSalman Rushdie’s novels have always felt to me like stepping into an Indian Mughal miniature painting where several things are happening at once. “For me the fantastic has been a way of adding dimensions to the real,” he writes, “adding fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh dimensions to the usual three; a way of enriching and intensifying our experience of the real, rather than escaping from it into superhero-vampire fantasyland.” With its carousel of shifting politics and history, Victory City is Rushdie’s most textured and triumphant wonder tale yet. Unlike the authors of the epic poems Rushdie is so clearly doffing his hat to in Victory City — Valmiki and Vyasa — of whom we have scant biographical details and whose lives have little relationship to their work, the events of Rushdie’s life are constantly being tied to his work, no matter how fantastical. For those of us who see Rushdie as a champion of free speech, Victory City is not just a restoration of the powers of fiction in these censorious times, it is also a reminder that fiction remains one of our most potent ways of asking how we must live. And while there is something celebratory about the ultimate victory of the word in Victory City, the novel, with all its mythic qualities, seems to be urging us to turn away from this insistent need to connect the life to the work, to cut poems and stories free from their makers and allow them to float freely.

History of this topic

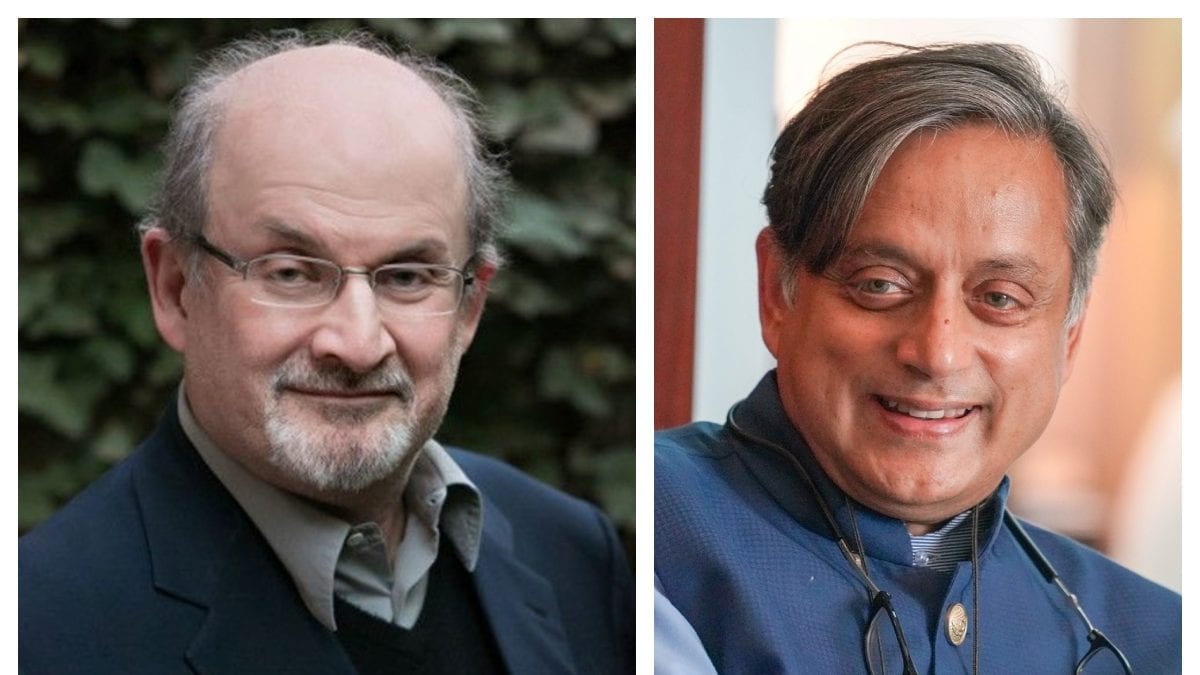

Salman Rushdie "Greatest Living Indian Writer, Nobel Long Overdue" Says Shashi Tharoor

News 18

Book Review: ‘Victory City’ by Salman Rushdie

The Hindu

Review: Victory City by Salman Rushdie

Hindustan Times

Shobhaa De | Why time for ‘maun vrat’ is over: Silence not an option

Deccan Chronicle

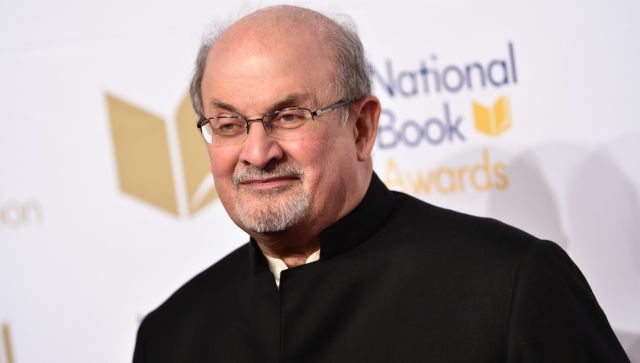

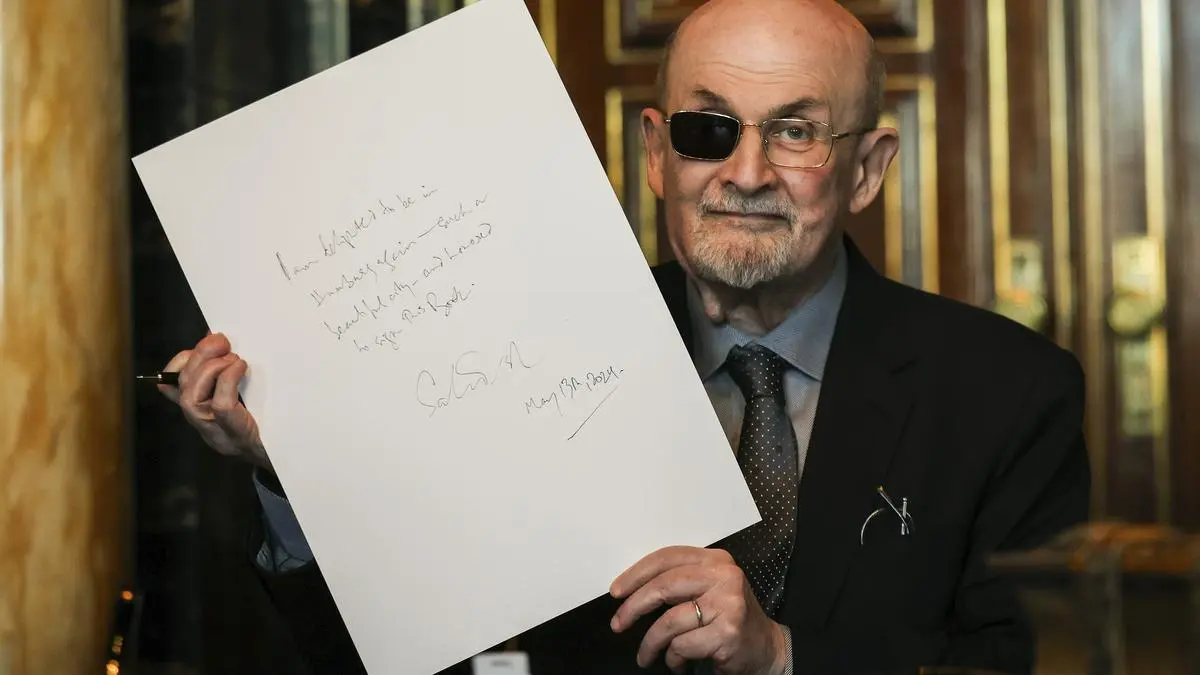

Salman Rushdie uploads selfie, months after losing an eye to Islamist Jihadi attack

Op India)

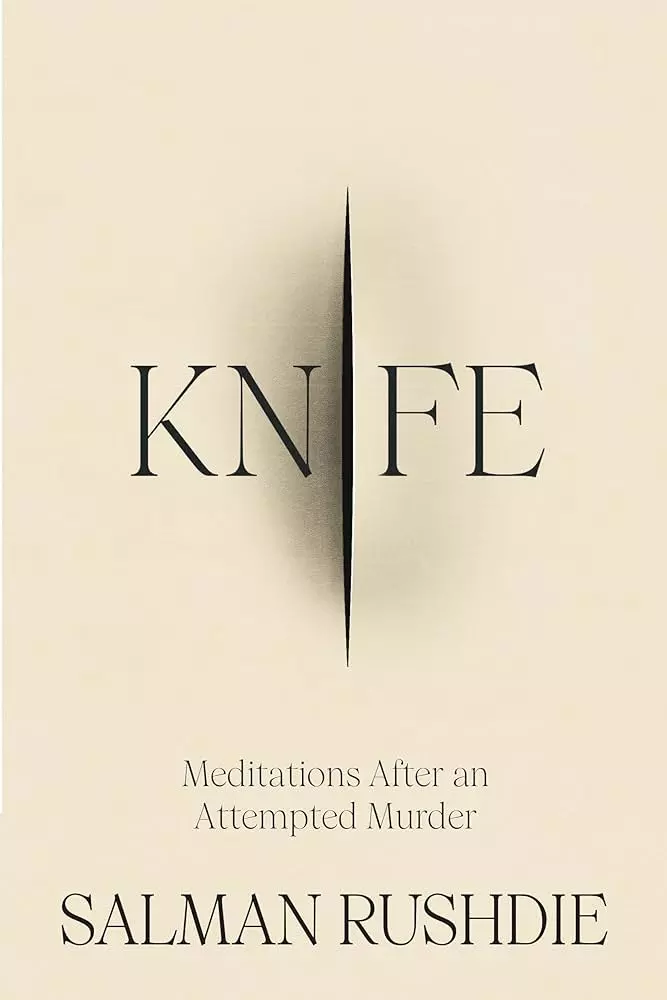

Salman Rushdie releases new novel, six months after knife attack

Firstpost

Book review | ‘Victory City’ is carried forward by Salman Rushdie’s infectious energy

The Hindu

Salman Rushdie’s new novel reminds us how his writing changed the world

LA TimesDiscover Related

)

)