What’s Fact and What’s Fiction in Mary and George

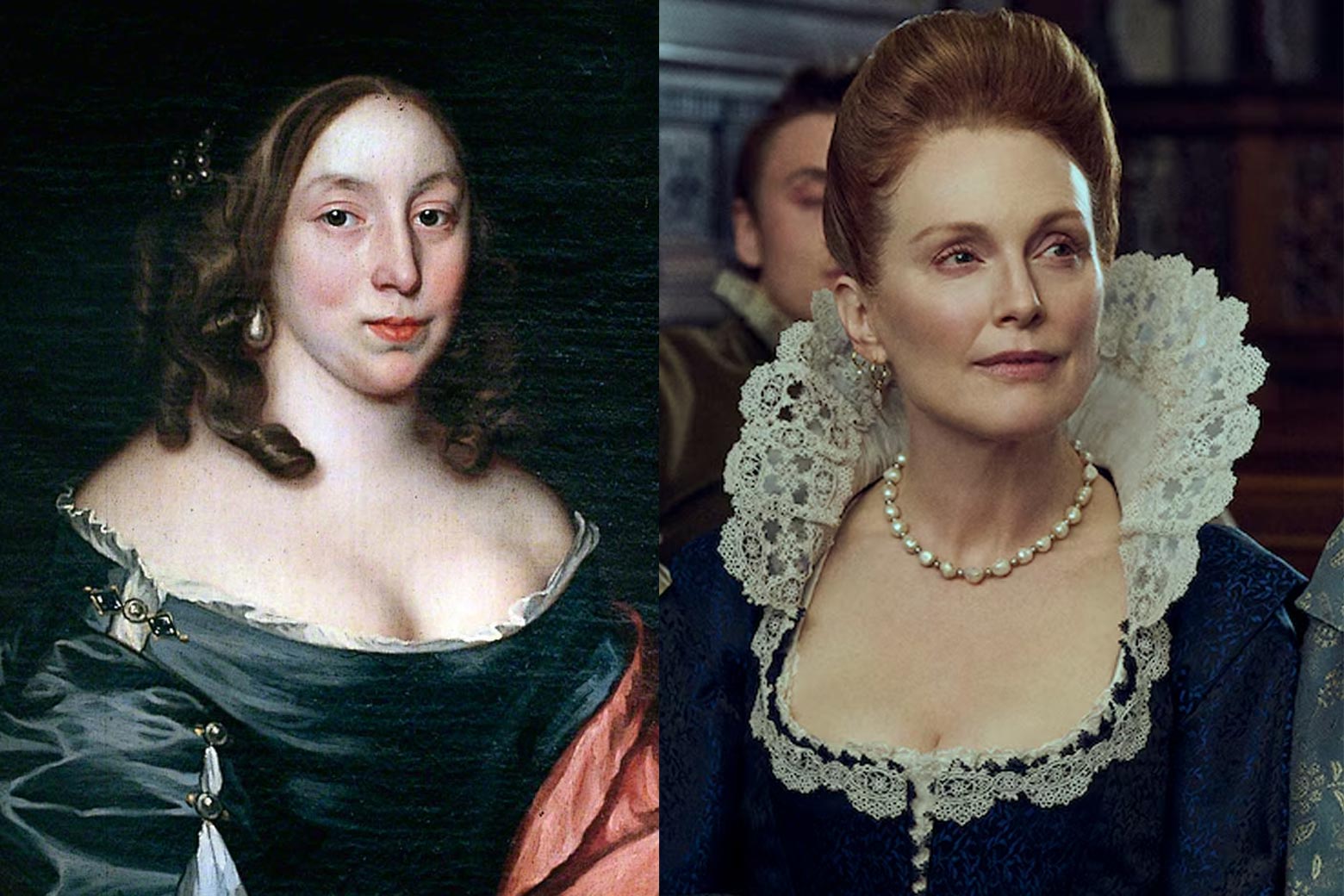

SlateMary and George—a dramatization of the stratospheric rise of the Villiers family to power and influence during the reign of Elizabeth I’s successor James I—is one of the new breed of period dramas like The Great or The Favourite, where, apparently unconstrained by the rigid social mores, constricting formality of dress, or religious edicts of their time, characters behave like contemporary privileged libertines, indulging in ripe swearing and over-the-top sexual activities. In truth, Mary was never a lady’s maid, which would have made her a servant, but she was, said Woolley, a “waiting woman” to one of her relatives, a waiting woman being “sort of between service and gentry, so she occupied this rather ambiguous social rank.” A good analogy might be the Victorian “companion,” usually a somewhat impoverished spinster or widow who had no household of her own and was taken in by a more affluent relative to be a sort of personal assistant/dogsbody to the mistress of the house. In 1618, the Venetian ambassador reported home that “the King honoured with marks of extraordinary affection, patting his face,” while the French ambassador, quoted in Michael Young’s King James and the History of Homosexuality, asserted that he “had too much modesty to report everything” he saw in graphic detail, comparing James’ retreats to the English town of Newmarket with his coterie of Ganymedes to the dissolute Emperor Tiberius’s notorious sojourns on Capri. Another letter from the Venetian ambassador observed that “the King has given all his heart, who will not eat, sup or remain an hour without him and considers him his whole joy,” while a member of Parliament named John Oglander noted he “never yet saw any fond husband make so much or so great dalliance over his beautiful spouse as I have seen King James over his favorites, especially the Duke of Buckingham.” Moreover, when Villiers was made a privy councillor in 1617 at age 24, James made a speech saying, “You may be sure that I love the Earl of Buckingham more than anyone else,” and later that year sent Villiers a portrait of himself with his heart in his hand along with passionate letters addressing Villiers as his “sweet heart.” While no definitive proof exists that the relationship was fully sexual, a restoration of James’s residence, Apethorpe Palace, in 2008 revealed a previously unknown passage linking the king’s and Villiers’ bedchambers.

Discover Related