The UN Report on China’s Detention of Minorities in Xinjiang

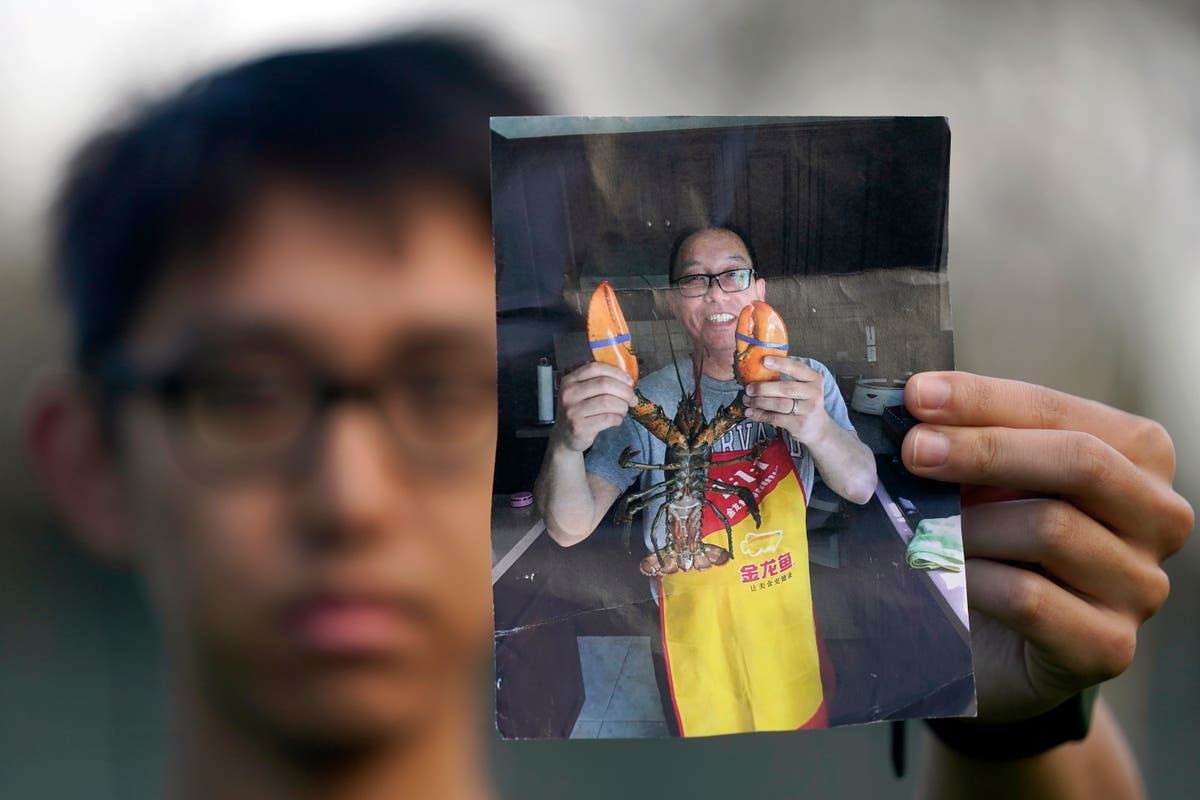

The DiplomatIn 2018, fresh off her second stint as Chile’s president, Michelle Bachelet took on the job of High Commissioner of the United Nations Office for Human Rights. The Report The report – officially the “OHCHR Assessment of human rights concerns in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region” – is 48 pages long, including its extensive footnotes. The premise prompting the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights to research and report upon the situation in Xinjiang was the “increasing allegations” it began receiving “from various civil society groups that members of the Uyghur and other predominantly Muslim ethnic minority communities were missing or had disappeared” in Xinjiang. Indeed, the U.N. report finds that the “China Cables,” the “Xinjiang Papers,” the “Karakax List,” the “Urumqi Police Database,” and, most recently, the “Xinjiang Police Files,” most of which are now in the public domain, “are highly likely to be authentic and therefore could be credibly relied upon in support of other information.” Throughout the report, the authors are careful to tie its findings and interpretations to existing and established principles already codified in international law. And I can tell you that the principle of Do No Harm applies just as much to the responsibility of political leadership as it does to the discipline of medicine.” In the end, Bachelet must have realized that sparing the face of the Chinese leadership by quashing the report would violate her own stated basic principle of political leadership, “Do No Harm.” Smothering the report and preventing a public viewing would irrevocably further harm the victims of China’s genocidal campaign against the Muslim minorities of Xinjiang, by denying them the international validation that their dehumanizing and deadly experiences had occurred.

History of this topic

UN members condemn China over abuse of Uighurs in Xinjiang

Al JazeeraExplained: What does the U.N. report say about China’s repression of Uyghurs in Xinjiang?

The Hindu

Michelle Bachelet | The champion of rights

The Hindu

U.S. slams China on human rights violations in Xinjiang, vows to hold Beijing accountable

The Hindu

US slams China on human rights violations in Xinjiang; vows to hold Beijing accountable

India TV News

To China’s fury, UN accuses Beijing of Uyghur rights abuses

Associated Press)

Explained: Why China is livid over UN report on atrocities on Muslim minorities in Xinjiang

Firstpost

EXPLAINER: Why is China so angry over UN report on Xinjiang?

Associated Press

EXPLAINER: Why is China so angry over UN report on Xinjiang?

The Independent

'Crimes Against Humanity', Glaring Omission & Timid Timing: Decoding UN Report on Xinjiang Abuses

News 18

UN finds possible ‘crimes against humanity’ in report on China’s Xinjiang

The Independent

UN cites possible crimes vs. humanity in China’s Xinjiang

Associated Press

UN releases report on possible crimes against humanity in China\'s Xinjiang

Deccan Chronicle

UN cites possible crimes against humanity in China’s Xinjiang

The Independent

Potential ‘crimes against humanity’ in China’s Xinjiang, UN says

Al Jazeera

Uighurs demand accountability after UN report on China abuses

Al Jazeera

Much awaited UN report on China says possible crimes against humanity in Xinjiang

India TV News

UN, China present opposed reports on Uighurs in Xinjiang

Al JazeeraUnited Nations report on Xinjiang backs fears felt by Australia's Uyghur community

ABC

U.N. cites possible crimes against humanity in China's Xinjiang

The Hindu

U.N. cites possible crimes against humanity in China’s detention of Uyghurs in Xinjiang

LA Times

UN rights chief admits 'tremendous pressure' over Xinjiang report

The HinduChina reportedly seeks to stop U.N. rights chief from releasing Xinjiang report

The Hindu

UN rights chief admits she wasn’t allowed to speak to a single current Uyghur detainee during Xinjiang visit

The Independent

Dozens of countries question China at UN over Xinjiang ‘abuses’

Al Jazeera

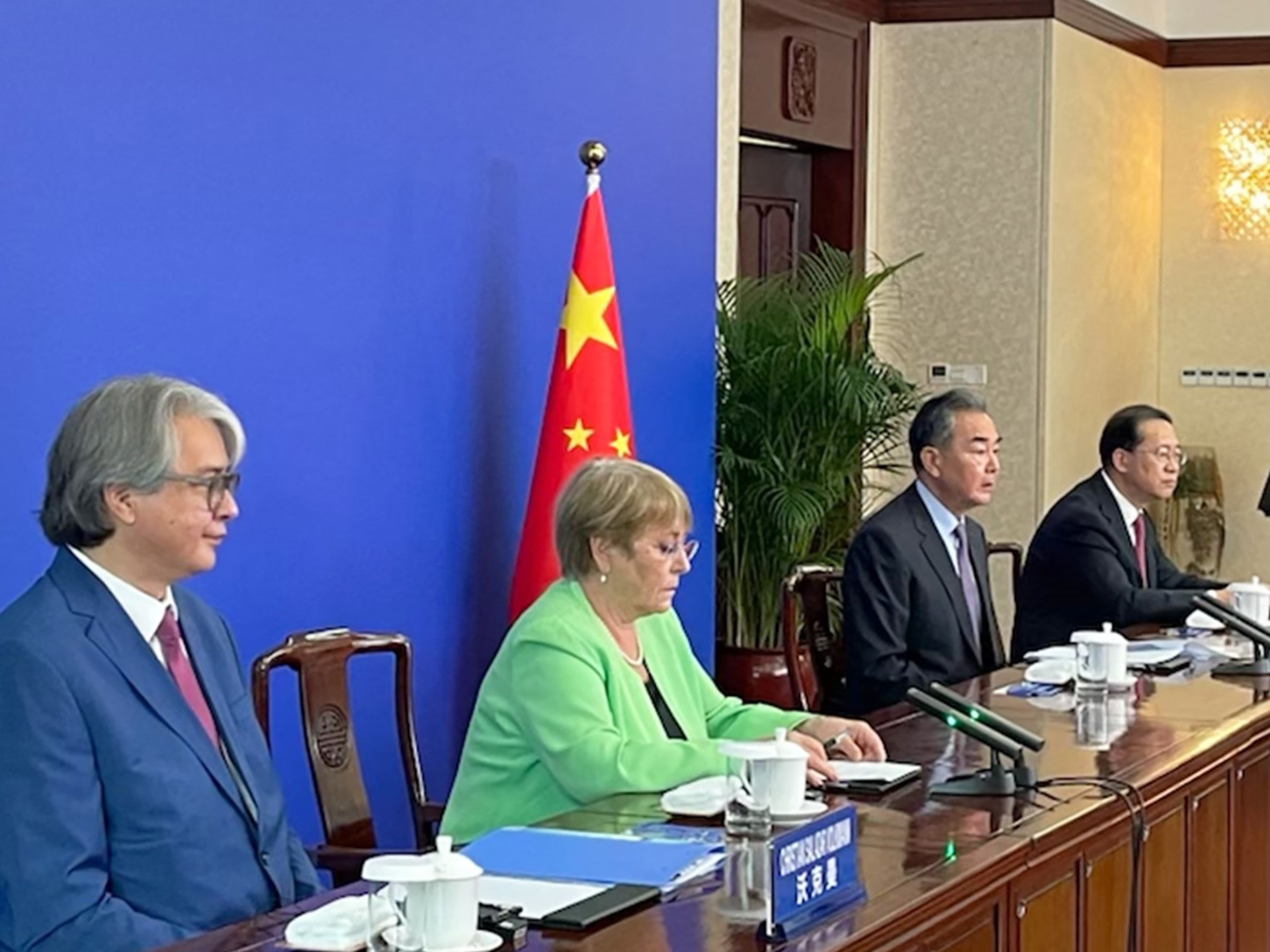

UN human rights chief asks China to rethink Uyghur policies

Associated Press

U.N. human rights chief asks China to rethink Uighur policies

The Hindu

UN’s Bachelet says China trip not for a probe, faces criticism

Al Jazeera

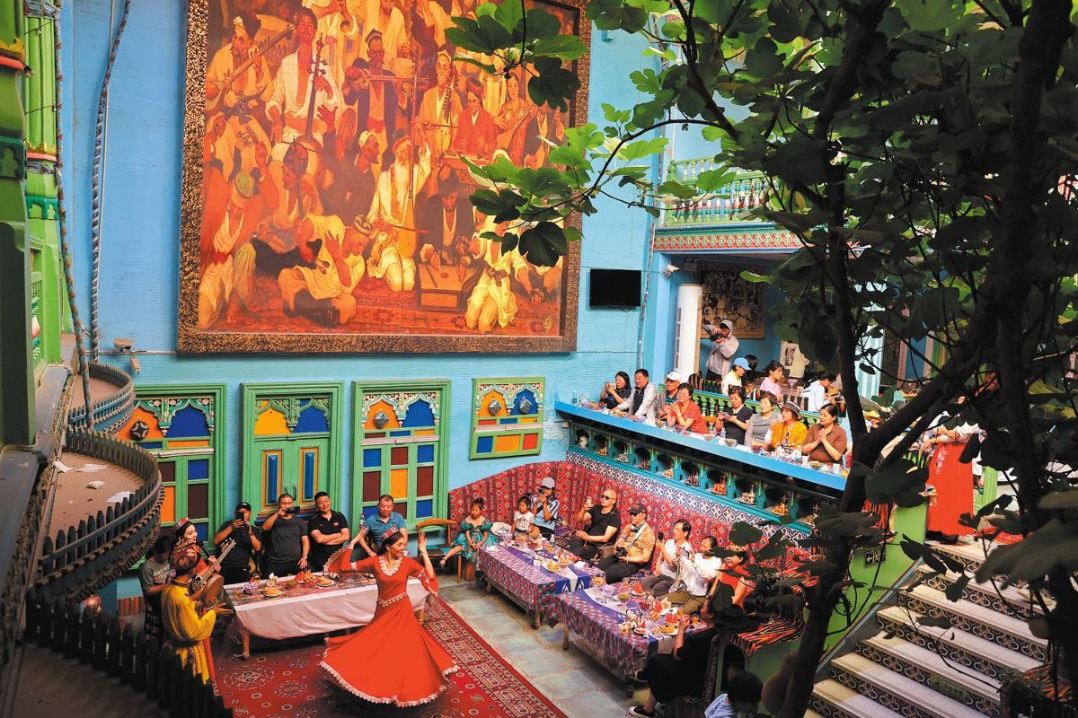

No Need for Patronising Lectures, Xi Tells UNHRC Chief as She Heads to Xinjiang to Probe Uygurs Rights Violations

News 18

Xi defends China’s record during talks with UN human rights chief

Al Jazeera

China hopes UN rights chief's visit will ‘clarify misinformation’

Hindustan Times

Xinjiang leak reveals extent of Chinese abuses in Uighur camps

Al Jazeera

What will the UN see as it finally visits China’s Xinjiang?

Al JazeeraXinjiang in focus as U.N. rights chief arrives for China visit

The Hindu

Xinjiang in focus as UN’s Michelle Bachelet visits China

Al Jazeera)

China's crackdown of Muslim minorities under scrutiny ahead of UN human rights chief visit

Firstpost)

‘Failing to stand up for Uyghur community’: US slams UN human rights commissioner for Xinjiang trip

FirstpostUN High Commissioner for Human Rights to visit China's Xinjiang region

ABC

UN Rights Chief to Visit Xinjiang in May as Groups Press for Report

News 18

US Holocaust Museum says China ‘may be committing genocide’

Al Jazeera

Bachelet seeks Xinjiang trip amid reports of Uighur persecution

Al Jazeera

Bachelet reports arbitrary detention, sexual violence in Xinjiang area of China

Hindustan Times

UN rights chief decries abuses in Xinjiang, arrests in Hong Kong

Al Jazeera

China rejects Uighurs genocide charge, invites UN’s rights chief

Al JazeeraDiscover Related

)

)

)

)